NATHAN: You started talking about your Land Arts program. Now we know a little bit where it kind of started… how would you define that in a couple of sentences for somebody who doesn’t know what you do?

CHARLOTTE: I’m sorry, just a quick thing. I didn’t know that there was another Land Arts program in New Mexico. So I’m also curious to know what are the similarities and how are they different?

Chris: So Land Arts of the American West began actually in 2000 at the University of New Mexico. Bill Gilbert and John Wenger, two artists, got the ball rolling. And Bill, for a bunch of years prior to that had been teaching a summer indigenous ceramics workshop in Northern Mexico, in Chihuahua, in Mata Ortiz. I had known Bill from when I was living in New Mexico. We are personal friends and professional friends as well, so we stayed in touch. So after that first run, he and I were talking and there was a clear connection between art and architecture … prompting something bigger than just an art conversation. If it’s about the land and being out there, then these other layers come through. Also, if you’re going to be out in that intense kind of a way, it matters who you travel with and how you construct the team. So, we had a good relationship and started. For me, the DNA of the Land Arts program overlaid a great many things in my background, personal and professional, and so it was a real easy fit. The program began as a joint program [between UT Austin and UNM] and ran from 2002-2008. Then we split and that program has continued to go forward just as the Texas Tech program has. They’ve defined their agenda on their own terms, primarily around an Art and Ecology MFA.

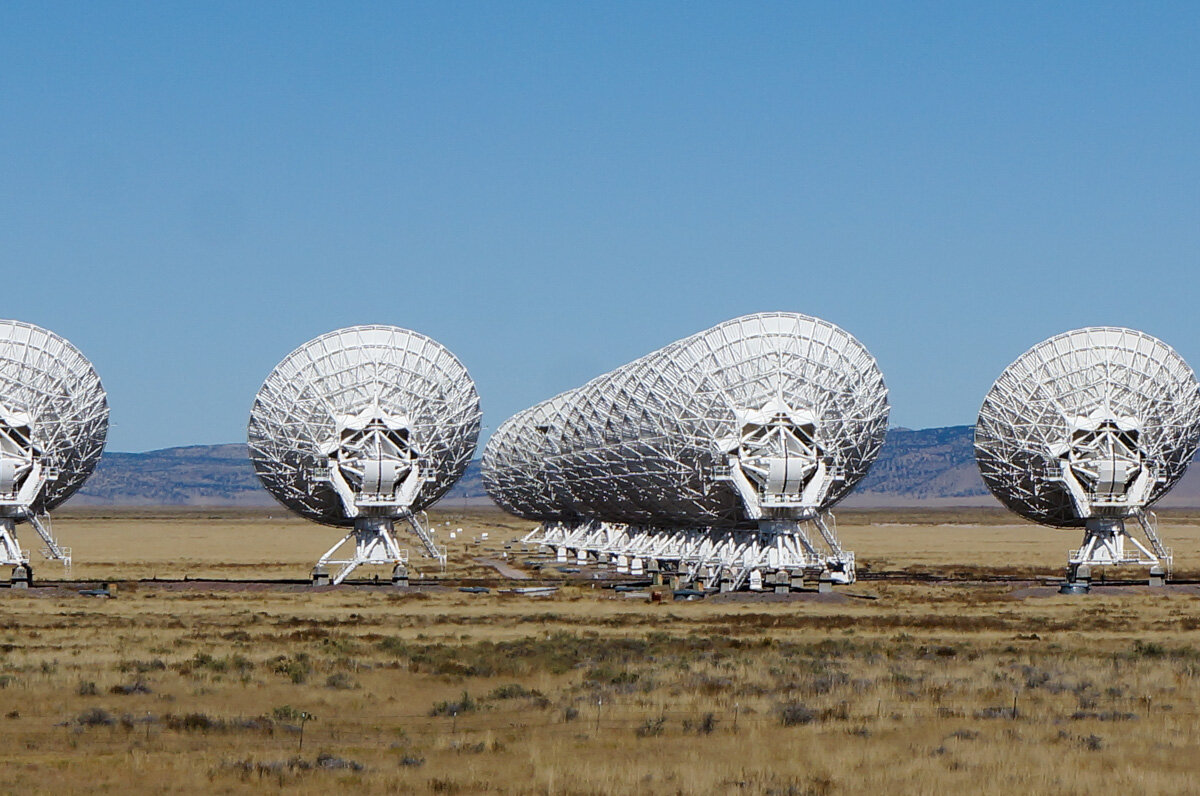

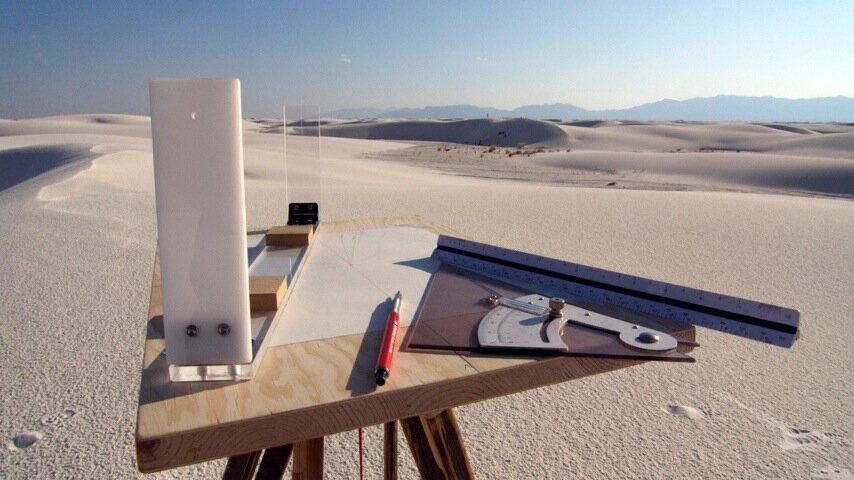

The Land Arts of the American West at Texas Tech is basically a semester abroad in our own backyard. It’s an immersive, studio-based, field program that run in the fall semester. It attracts architects, artists, writers, a wide range of people to travel together and make their work in the field, and make their work in response to the wide range of things we see. As an architect, I define land art very broadly. It’s not just things in art history with the capital A in front… If we think about art as cultural expression, then this is cultural expression situated within land. It’s things that have emerged for aesthetic reasons but also, we can look at things that have emerged from industrial reasons, from cultural reasons, from all sorts of other motivations. We’ll observe wilderness areas, a toxic former open pit mine, a scientific installation, all of these are forms of expression of human activity on the land.

NATHAN: Hydroelectric dams and power poles and lines. Settlement patterns…

Chris: Totally. I may have said before that throwing trash out the window of your car as you’re driving down the road is a cultural expression. We could say, “Hey, that’s art.” Not necessarily aspirational, but it’s an expression of your relationship to the land and what that relationship is. In that it can be instructive and we can learn from it.

The other key piece of the program is that we go out there. This comes a bit from the importance in my background of the work of JB Jackson, the landscape historian who started Landscape Magazine. Jackson said, “If you’re going to study the landscape, you can’t just study the proper garden and formally designed things, you have to study the trailer park and the alley -- all of it.” Everything’s in the frame. We don’t just get to say the button on the jacket is the thing. It’s the jacket, it’s the jacket on the person, it’s the jacket on the person in the room, it’s the jacket on the person in the room in the building in the territory. . .

NATHAN: It’s who made the jacket. Where’d the fibers come from that made that jacket...

Chris: Exactly. If you take that attitude of “everything’s in,” then the challenge becomes: What are your questions? What are your responses relative to what you’re seeing in the world that you’re inhabiting? A key tenet of the program is that we go see these things. We spend about two months camping and traveling about 6,000 miles in that time, and we see a wide range of things. Ultimately we process what we’re seeing, and talking and thinking about, through our work. Everybody brings a question or a set of questions and everybody produces a body of work and everybody’s body of work has a different shape and agenda and manifestation. Each participant determines that for themselves and in conversation with the group. The way I like to think of and describe the program to participants and others is as if it’s a stage. It’s a setting. It’s a situation. And making it possible for the people to do what they need to do on that stage is my role. So I’m a bit of a choreographer, charging in at certain moments or other times letting the pressure off so people can reflect and make work in different ways. My role is not to try to produce. We’re not a factory producing land artists, or derivative land artists. Our goal is to use land art to think with and about how humans interact with each other and the landscape. In that, it’s super generative and open and can lead out to places that I for one, can’t anticipate. Generally, anybody in the group at any given moment can anticipate where this is going. We’re all committed to being on that journey together.

NATHAN: I’m totally fascinated by the program and I wish, I hope, that some day I can do the whole thing with you, or at least a little stretch. I don’t know when that’s going to happen at this point.

Chris: We just posted the application information for 2021. It just went live on the website yesterday.