Chris Taylor

Chris Taylor is the Director of Land Arts of the American West and is an Associate Professor of Architecture at Texas Tech University in Lubbock, where he has been since 2008. He studied architecture at the University of Florida and the Graduate School of Design at Harvard. We have known Chris since 2017 and are so excited to feature his voice in our NE PLUS ULTRA series. His program Land Arts of the American West is an important program - uniquely of its time and place, and profound as a vehicle for the fortunate participants and their work - and, we feel it epitomizes not only many of the directions we love to explore in our work. The list could be long, but interdisciplinarity and site-specificity come to mind, as well as relationships both internal and external, and in relation to a stomping ground we too have enjoyed, between the the Great Salt Lake and deep/south West Texas. Currently, Chris splits his time between Marfa and Lubbock, Texas and we are grateful that we managed to entice and capture him in Marfa, to spend a couple of hours with us in January.

One Lubbock night, following the car below, Chris led us from La Sirena to Terry Allen’s Stubb’s Memorial and it changed our lives just right. We hope you enjoy the conversation and images below!

Chris: So I should go change my costume or background. Should I put on a groovier background?

Charlotte: No. I love that background, it’s brilliant.

Chris: Okay.

NATHAN: We assume you, like us, have spent a lot of time in isolation, or in a new range or limit of environments compared to a year ago. Charlotte and I are in Canada as we record this, which has not been quite so extreme on so many levels as different parts or communities in America… But we have been on our own a lot. So we have reached out to friends and colleagues on occasion beyond the day to day work world, and have found these conversations quite valuable. Not only because it’s nice to see people, but there’s always so much to talk about, for better or for worse. To see what people are going through in their different worlds and their perspectives on it. Everything looks a little different, and I don’t really know the world that we live in right now.

So… How are you doing?

Chris: The plasticity of time. That’s been a big thing, that plasticity. . . to feel decoupled and totally free flow and then be jammed up. Since last March, we’ve been having... We call them COVID cocktails on Saturday at 5:30 with some friends. A couple in New York and a couple in St. Louis. And it started off just as, like, what is this? What’s happening? And then it became a bit of a lifeline of, where we all look forward to checking in... And it’s just an hour, occasionally it will go a little longer. It’s kind of a check-in, and has been really helpful. What’s happening at your school? What’s happening in your city? How can you still be in Texas? You know, all of the questions.

NATHAN: You’re in a great part of Texas.

CHARLOTTE: Yeah, you’re in a good part.

We do have video. Chris in Marfa. Nathan and Charlotte in Vancouver.

…

CHARLOTTE: First, we’re so excited about having you participate in this series which encompasses a lot of different people whose work we admire, and who we adore as human beings, and whose voices we think are important to feature.

NATHAN: And whose work might crossover in some realm with our work and interests.

CHARLOTTE: So we sent you a list of questions. And I thought we’d go through them loosely… to start out with, can you tell our readers and our viewers a little bit about your background?

Chris: Yeah. So, a little bit about my background. My father was in the army, so I happened to be born in Germany but did most of my growing up on a high spot of ground between the Everglades and the Gulf of Mexico in Southwest Florida. I did a lot of coming into the world, in an aqueous world. And for some reason, and I don’t know whether it was just a subliminal plot of my mother or what, but early on I was like, “Architecture is the thing. I’m gonna be an architect.” Even though I had no idea what that meant. I remember going off to my freshman year in college thinking I had all the answers and knew everything about architecture. And then we were told to find a door on campus and draw it. “Draw?” “I don’t sketch. I can draft anything.” I remember that first day being this... first kind of explosion, a disciplinary explosion, about expectation versus moving into what the discipline really is. And the curious thing, of course with a little bit of nostalgic reflection, is the acknowledgement of, “Oh. This is different than what I expected, and it’s more interesting.” And I was drawn in deeper. And I would say with every turn throughout my education and since, it hasn’t been about following a single preexisting path and getting to this cheese, and then getting to that cheese, and “oh this cheese is a little bit better than that cheese.” It’s coming into a situation, and leaning in, or helping it be that thing that’s beyond expectation. And so that’s also allowed me to end up in this place where I do what I do. That didn’t necessarily come from some pro forma preexisting condition.

…

So yeah, there’s a short answer and a long answer. When I first landed in Arizona, [at Tucson] there was an informal lunchtime lecture series that asked me to give a talk to introduce myself. Since I had already lived in a few places at that point, I organized the talk by all the zip codes that I had lived in as a way to tell the story of how I ended up in Arizona. It was a bit circuitous. Right after graduate school I got into teaching at the University of Florida, my undergrad alma mater, for a year. And that led to a tenure track position in Fargo, at North Dakota State. Which was really interesting, and a landscape that actually has some similarities to the Llano Estacado in terms of its geologic horizon. People were wonderful too. There was great opportunity, but at the same time, there were two concerns. One was I had a young family and signing up other people for a life on the tundra in an isolated research camp seemed a little harsh. And also, I had seen people move straight into teaching and develop a gap between the practice of architecture, and the teaching. I was somebody that, particularly in my graduate education, developed a real deep commitment to fabrication, to building, to actually making what I designed. I wanted to get my hands dirty. So, I left. This kind of classic foolish thing to do was in the height of a recession. I resigned my tenure track position and put all my stuff in storage and drew a big loop on the map heading down into New Mexico over Southern California, up around Pacific Northwest, and then back to figure out where we would move. This was 1992 so there was no work on the East Coast or the West Coast. Everybody was laying people off. We got to New Mexico and we were tired of driving so we never finished that big loop in that go.

We ended up checking out the places that we were interested in later but in that episode, we stopped in New Mexico. I practiced there for three years. Then moved to Austin in an Airstream trailer with five sheep and two dogs and two other people. Practiced there for two years and then moved back to Southwestern Florida for a job also in practice. And that launched a fellowship award, a research competition that gave me funding to spend a year abroad -- in Venice, Italy. This is all way too long and detailed, and not interesting to any readers out there, but...

NATHAN: It is.

CHARLOTTE: I am curious about the five sheep.

NATHAN: Yeah, I want to... I have 40 questions now.

Chris: That opened the door to get back into teaching, which is how I ended up in Tucson. Which was a school going through a transformation. Super interesting. But then I was recruited to join the Art Department at the University of Texas at Austin, which was a position I had actually interviewed for when interviewing for the permanent gig in Tucson. Two years later, they reached out with a new position that surprisingly lined up with my experience. This was right at the moment when the conversation about the Land Arts program was emerging. So I moved to Austin and was within the art department in an interdisciplinary design program. That became an ideal crucible for building the Land Arts program with more flexibility than operating within an accredited architecture program. Even though it was really hard to leave Tucson. Both the school and the Sonoran Desert were big magnets for me.

The Austin run was really great but it ran its course for a variety of reasons. I was on the market again and ended up in Lubbock bringing Land Arts back to my disciplinary home in the College of Architecture at Texas Tech University. But also keeping connections to artists, writers, people outside of architecture, which remins really important. At that point, the Land Arts program, which had been a joint program between two universities – split with a version of it in New Mexico and the version at Texas Tech. The split allowed each version of the program, to cultivate its strengths. I kinda feel there’s been three arrivals in Texas, but there’s really just two ‘cause the Austin-to-Lubbock is more contiguous.

When I first moved with those sheep in that Airstream... we were living in this little village in the mountains between Santa Fe and Albuquerque and all our crazy hippie friends were like, “How can you move to Texas, man? That’s like, oh, it’s gonna be crazy. You’re not gonna handle it. You’re moving to the dark side.” My response right away was, “Well, there’s actually compelling things there.” As a kid growing up in the suburbs of Southwest Florida, a place that had a real and active connection to land was very compelling, whether that was the rancher or the oil field worker or the farmer. There still was a land-based economy and cultural identity that was compelling. For me that’s the political landscape versus the cultural landscape. We can differentiate. Landing in an island like Austin was a much different point of entry than other places. But that was interesting, and for me it’s ultimately what’s kept me here. It’s been about what facilitates and propels the work. Texas has been a really great laboratory environment for the work I do. And part of that work is embedded or vested in the experience that once you move out into the land, once you move into the landscape and this hybrid between what the ground is and what people do with it. It’s super complicated and it’s super interesting, and you can’t put a single explanation over it. Generalization is the antithesis to operating in landscapes. So that a place like Texas, with all of its warts and complexities and things that, you’re like, “Oh, this is not a good taste in my mouth.” That is actually sustaining... That provides productive traction.

CHARLOTTE: I’m just curious, how long have you been at Texas Tech?

Chris: I arrived at Texas Tech in 2008.

NATHAN: You started talking about your Land Arts program. Now we know a little bit where it kind of started… how would you define that in a couple of sentences for somebody who doesn’t know what you do?

CHARLOTTE: I’m sorry, just a quick thing. I didn’t know that there was another Land Arts program in New Mexico. So I’m also curious to know what are the similarities and how are they different?

Chris: So Land Arts of the American West began actually in 2000 at the University of New Mexico. Bill Gilbert and John Wenger, two artists, got the ball rolling. And Bill, for a bunch of years prior to that had been teaching a summer indigenous ceramics workshop in Northern Mexico, in Chihuahua, in Mata Ortiz. I had known Bill from when I was living in New Mexico. We are personal friends and professional friends as well, so we stayed in touch. So after that first run, he and I were talking and there was a clear connection between art and architecture … prompting something bigger than just an art conversation. If it’s about the land and being out there, then these other layers come through. Also, if you’re going to be out in that intense kind of a way, it matters who you travel with and how you construct the team. So, we had a good relationship and started. For me, the DNA of the Land Arts program overlaid a great many things in my background, personal and professional, and so it was a real easy fit. The program began as a joint program [between UT Austin and UNM] and ran from 2002-2008. Then we split and that program has continued to go forward just as the Texas Tech program has. They’ve defined their agenda on their own terms, primarily around an Art and Ecology MFA.

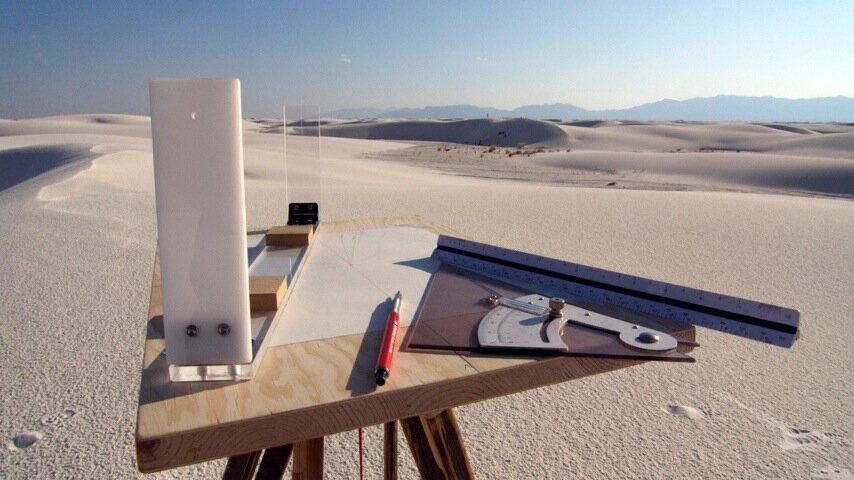

The Land Arts of the American West at Texas Tech is basically a semester abroad in our own backyard. It’s an immersive, studio-based, field program that run in the fall semester. It attracts architects, artists, writers, a wide range of people to travel together and make their work in the field, and make their work in response to the wide range of things we see. As an architect, I define land art very broadly. It’s not just things in art history with the capital A in front… If we think about art as cultural expression, then this is cultural expression situated within land. It’s things that have emerged for aesthetic reasons but also, we can look at things that have emerged from industrial reasons, from cultural reasons, from all sorts of other motivations. We’ll observe wilderness areas, a toxic former open pit mine, a scientific installation, all of these are forms of expression of human activity on the land.

NATHAN: Hydroelectric dams and power poles and lines. Settlement patterns…

Chris: Totally. I may have said before that throwing trash out the window of your car as you’re driving down the road is a cultural expression. We could say, “Hey, that’s art.” Not necessarily aspirational, but it’s an expression of your relationship to the land and what that relationship is. In that it can be instructive and we can learn from it.

The other key piece of the program is that we go out there. This comes a bit from the importance in my background of the work of JB Jackson, the landscape historian who started Landscape Magazine. Jackson said, “If you’re going to study the landscape, you can’t just study the proper garden and formally designed things, you have to study the trailer park and the alley -- all of it.” Everything’s in the frame. We don’t just get to say the button on the jacket is the thing. It’s the jacket, it’s the jacket on the person, it’s the jacket on the person in the room, it’s the jacket on the person in the room in the building in the territory. . .

NATHAN: It’s who made the jacket. Where’d the fibers come from that made that jacket...

Chris: Exactly. If you take that attitude of “everything’s in,” then the challenge becomes: What are your questions? What are your responses relative to what you’re seeing in the world that you’re inhabiting? A key tenet of the program is that we go see these things. We spend about two months camping and traveling about 6,000 miles in that time, and we see a wide range of things. Ultimately we process what we’re seeing, and talking and thinking about, through our work. Everybody brings a question or a set of questions and everybody produces a body of work and everybody’s body of work has a different shape and agenda and manifestation. Each participant determines that for themselves and in conversation with the group. The way I like to think of and describe the program to participants and others is as if it’s a stage. It’s a setting. It’s a situation. And making it possible for the people to do what they need to do on that stage is my role. So I’m a bit of a choreographer, charging in at certain moments or other times letting the pressure off so people can reflect and make work in different ways. My role is not to try to produce. We’re not a factory producing land artists, or derivative land artists. Our goal is to use land art to think with and about how humans interact with each other and the landscape. In that, it’s super generative and open and can lead out to places that I for one, can’t anticipate. Generally, anybody in the group at any given moment can anticipate where this is going. We’re all committed to being on that journey together.

NATHAN: I’m totally fascinated by the program and I wish, I hope, that some day I can do the whole thing with you, or at least a little stretch. I don’t know when that’s going to happen at this point.

Chris: We just posted the application information for 2021. It just went live on the website yesterday.

NATHAN: I’m glad you’re doing it, and hoping the pandemic has cleared enough by the fall to not restrict you all too much. Can you tell us what your territory is for the program? Where would you travel to typically? And could you paint a picture of a typical day?

Chris: The itinerary is determined by certain sites that are super instrumental and necessary. So those are pins on the map, and the journey between those pins is essential. And one of the goals is to experience as much of the diversity of the American West as possible. The American West isn’t all coyotes and roadrunners like the cartoon. There’s forested mountain tops, saline dry lake flats, a really wide array of types of landscapes. That’s also an objective. We leave from Lubbock and travel through New Mexico, Utah, Nevada, Arizona, and back through New Mexico and West Texas. We take a month-long first journey that usually covers more miles and swings a little farther north because it’s still early in the year and we are dealing with light and temperature in our itinerary. We swing up and around the top of the Great Salt Lake to visit the Spiral Jetty and Sun Tunnels and then come down the eastern edge of Nevada to visit Double Negative, and then usually work our way back across.

One of the things about that first journey, being more adventurous in terms of the number of miles, is we tend to move a bit more quickly. We start off with a couple of days here, a couple of days there, and so we’re leapfrogging through the territory. We’re also learning how to set up camp and take down camp, and it’s kind of an introduction to how this all works. By the end of that first week, we’ve had time traveling but we’ve also had time learning how to figure out a new place, figuring out what the opportunities or hazards are, how to set up and take down. That collective responsibility of looking after and setting camp is also part of the pedagogy. Getting everybody on board with that is key.

In the second month we tend to stay a little more southern. In the latitude we head across Southern New Mexico and Southern Arizona, and then also Southwest Texas is part of the puzzle. And in that second journey, we tend to move a little slower. We stay at places longer and so there’s more time for work production. It’s not as frenetic. We are met by field guests at different sites to help either explain or interpret places that we are at, or who serve as examples, giving talks about their work as a way to help expand the realm of possibility.

There are three typical days in the Land Arts program. There’s a Travel Day where we have to get from here to there, we have to pack up, move and then unpack and set up camp. Some of those days, a three-hour travel time would be short. They can go as long as eight to 10 hours of road time. We tend to try to limit to eight hours of actual road time because that’s a lot, especially with a group of people stopping for the bathroom and fuel. On those travel days, we resupply with groceries, ice, propane, water. And there’s an orchestration about that, which is also a big part of the culture of the group, of everybody working to resupply and get on the road as quickly as possible. The second typical day happens at Interpretive Sites, such as at Chaco Canyon, where we are at a place to see what’s there. Generally we’re at a place like Chaco for two nights, sometimes three. We have a long day all hiking out to see the sites and we’re working... We’re there together in sort of a typical tour fashion.

And then the third day we call Work Sites. We’re at a place, and it may be a place of culture, like Wendover, Utah, where The Center for Land Use Interpretation has a base, or maybe it’s a wilderness site in a beautiful landscape and we’re there for four days and it’s a time to produce work. And so that’s the movement, from traveling together to the least structure of a work site. But always breakfast is at 7:00. We start with the sun and mostly end with the sun each day, because it’s all about light. And we come together at the beginning of the day or at the end of the day for meals. We have a communal kitchen, a food operation that’s pretty sophisticated at this point. Checking in and supporting each other is key - the safety and protection of the group biologically and culturally is super important. It’s one thing to go camping for a weekend and rough it, and it’s another thing to be on the ground and on the road for a month, have a week break and go for another month. The saturation is heavy duty. There’s an overall tiredness and depletion that happens. So, managing all that is key. Also, when we’re out there, we don’t have weekends, we don’t take breaks, it’s just... The time is really precious. We just go and go and go and go...

NATHAN: I can imagine that being... I’m thinking of a meditation retreat in the sense that you’re a small group going through something together. It’s a little bubble, little stir-fry that you’re cooking there that you probably need be cautious how you let people... not run off to the city and see the museum as you’re passing through… let’s kinda keep everyone simmering just right...

Chris: Yeah, this would be whatever the opposite of retreat is, and then it would be maximalization instead of meditation, like instead of moving in, we’re moving out.

…

In 2019, we spent a longer time at Double Negative to create a laser scan of it. The work was 60 years old, and we had done a laser scan in 2009. To have those two data sets was something we wanted to do, but also there was somebody that wanted to hold a symposium around land art-related things at the University of Las Vegas. We all went into town and had Thai food for lunch and then went to campus to hear some lectures and be part of a more typical academic setting, which was interesting. When we come out of the field, we’re all like, “We went swimming in the lake yesterday, kind of, but that’s as good as it’s gotten for the last week in terms of hygiene.” And so that’s all very dynamic.

CHARLOTTE: Now I’m also curious in terms of how big is the group, usually? Do you have a number that an ideal number? And also just how do you choose the skill set or backgrounds of the students who participate? Is it important for you to get as much variety as possible in terms of people’s expertise?

Chris: Absolutely. One of the things that’s kept me pushing the interdisciplinarity or trans-disciplinary nature of the program is that if you bring a bunch of architects to go stand in front of a building and talk about it, everybody’s triangulating... Is it cool to like it? Is it cool not to like it? What am I supposed to say... What have I read, what am I supposed to do? And then it’s this kind of gamesmanship as to how that plays out, and that can happen with any discipline, right? But if you mix that up … and have people that don’t have all the same background, that’s just looking at it for what it is. It makes the conversation of the group super rich and, from my perspective, the more diverse and expansive the group the better. The big question for me with admissions is: Do you understand the opportunities, and adversities, and challenges of this experience and are you willing to throw yourself at them? And also, can you be productive in the process? Will this be productive for your work? That’s a question in the interview process, and often in that interview the person is amazing with a super clear trajectory of what their work is. And when we get in the field their work goes to some totally different place. And that’s fine. Because ultimately, it’s about the evolution of where they want to take their work. For me, that’s the big threshold on admissions, trying to maximize diversity and attract people that are ready for this experience to propel their work.

The number is limited historically by the number of seatbelts. Historically, we’ve just rented vans. One 15 passenger van for people which by state regulations we can only put 10 people in, and then a cargo van that has two seat belts in it. That’s where all the kitchen gear goes. This past year, we were super fortunate to receive a donation to acquire a truck that will be our kitchen vehicle. This spring and summer we are building out that truck. It’s the Land Arts Support Vehicle. It’s like an inside-out food truck. Instead of getting in the truck to cook, you stand outside. In the past, we’ve had a 10 foot by 40 foot shelter that we erect at each site and the kitchen comes out of the van and gets set up, and it’s in boxes and bins and tables and what not. The truck will do several things for us. It’s a vehicle that we can count on, with good tires. With rental vehicles you don’t always have control of that. It also has five seat belts and so ten plus five now gives us a threshold of 15 travelers. We tend to reserve a seat or two for guests, so generally we limit to 10 participants. Then there’s a program manager, an assistant that manages the kitchen and helps with the delivery of the program, and that historically, but not always, has been an alum of the program that’s then hired on to help run the operations. And so we’re a pretty tight group of 12 people total. Often though at various sites we’ll have guests. Often four to five extra people, some of them official, some of them just know where we are and want to show up for dinner. So, we tend to feed people wherever we go. When we’re in Marfa, our dining operation tends to grow as well because people want to come over for dinner. It’s great for the participants to interact with people as we travel and being able to invite people over for dinners is productive. So, the group is constantly expanding.

We also celebrate the exhibition at the end of the term, which happens the following spring. We host an even larger dinner in my workshop that expands to seat 99 people at one big table. That experience begins in the field. We move from the number of seat belts to how many people we can cook for, and ultimately, we celebrate the larger level.

…

NATHAN: I suspect it’s challenging to bring people and departments and academia together. I’m imagining the complexity of what you’re doing there. I think maybe as architects, we kind of have that side of us that likes data and spreadsheets and charts, and combining that with the mindset of those who go on a river trip for several weeks and have to pack their meat at the bottom of the cooler, to have it all staged out. I suspect it’s a fascinating exercise in its own right behind the scenes.

Chris: Totally. Another piece of this is, from the beginning, there was administrators that said, “Oh, this seems really great.” They get the visibility component. They get it even philosophically, and they are like, “This would be a nice summer thing you should do.” And from the beginning - and I don’t think we understood the power of our gesture at the beginning in answering that question, but I’ve come to really value it - we said, “No, this is way too important to be extracurricular. If we’re going to do this, it needs to be primary, to be a long semester.” That commitment and time and follow through on the part of the participants and everybody is super important.

NATHAN: Travel has always been so important to the architect’s education, to anyone’s education actually. I wish more people, Americans, did it in all fields, or had to in high school. I think of the classic one that you’re taught of in architecture schools, the grand tour, and think of the Land Arts of the American West as a variation of that. But appropriate to America, in its vastness, and, on the road, so many beautiful and uncomfortable things to see and learn from.

CHARLOTTE: I have to say, from a personal perspective, I remember seeing my first exhibition from your program and thinking, this is exciting! In academia, so many are set in their ways. But there’s a wonderful testament to creativity and a willingness to be open that I think is so desperately needed.

NATHAN: Charlotte would come if the special trailer has the Americano Espresso machine and New York Times delivery.

[laughter]

CHARLOTTE: And a shower. I don’t know, I like that.

Chris: One of the things about the... And this gets back a little bit to the accounting question, but we’ve... This all happens with a very meager budget and also, we have a limited footprint. You can only have so much gear personally, and we can only hold so much water. And water is super precious. So, we have enough for cooking and cleaning and, in recent years, we’ve started a tradition on the day before a move day that some of the water can be available for hair washing or bathing. It’s that balance of understanding finite resources. We need to also have some water reserved because we can’t be certain that we’re getting out of a given site, the conditioning of not counting on everything always working out and being prepared to get stuck for some time, and knowing that we will survive is important. With the new truck, it’s going to be able to hold a bit more. So, the potential to hold a bit more water and budget some of that water for bathing maybe possible. However, when I mention that to some alumni, they’re like, “No fucking way, you’re not having a shower.” They’re saying that because in their mind, that changes the whole ethos of the experience. Part of it is like, “If I had to suffer through this... “ But also it’s amazing how an annoyance is a thing to deal with. There’s ways to deal with it. It’s incredible how quickly concerns go away. There have even been people super freaked out or nervous about it going in and then after that first week, it’s like, “Oh, I figured out how to deal with this and it’s okay and I definitely am aware that I’m living in the world in a really different way than I would if I was at home having a shower every day.”

At a conference a few years back now in New York, at the College Arts Association, somebody asked a question about the lasting impacts on participants. I said, “That’s a great question. You should ask some of them ‘cause they’re in the room right now.” An art historian who was there stood up and said she still thinks about... how her daily shower is different now because of her time with Land Arts. She thinks about water. Even living in New York City, it’s a different animal and it’s a subtle, easy thing to say, a simple little cliche almost, but it also is a re-calibration about our relationship with the resource. Our relationship to each other, our relationship also to what’s important. Realizing like, “Oh, I really like bathing a lot but if I don’t and I’m in a group of people that... We’re all just dealing with that together, we can work this out, and it’s okay,” And that’s an amazing awareness and saturation place to get to.

CHARLOTTE: I just wanted to ask you as a conclusion: Now you’re sort of in Marfa. What are you doing there? Where does Marfa fit into your whole experience of West Texas, but also how does it fit into Land Arts and where you are and where you are going next.

Chris: So Marfa’s been a site in the land arts itinerary from the beginning. It’s important because of the legacy of Donald Judd’s work but even more so in the institutions that exist here. The Chinati Foundation, primarily, and also the Judd Foundation. This idea of deliberate and persistent fusing of art architecture and landscape, of situating specific works in specific buildings in a specific landscape. If you want to see that work you have to come to this place, you have to make the journey and see it in the conditions here. That’s a Land Arts gesture, by my definition. And so we’ve been coming here since the beginning because of that, and it’s super productive on all of those levels. And as the town has changed, it’s been interesting to see the evolution... There’s so few moments in our itinerary where we come into culture in a different way, and Marfa’s always been one of those. It has a very different energy than when we’re out just in total wilderness.

The Chinati Foundation - Marfa, Texas.

Within the last five years, the university expressed an interest in possibly developing a connection more formally to Marfa that’s manifested in certain programs in more focused summer workshops in art and in theater and dance. In architecture, we held a day-long symposium last year and a national conference a few years before that. There’s interest but it has yet to take on a more grounded presence. There’s been some talk, which I totally support, that the Land Arts program be based out of Marfa. The potential to think about what Spring offerings might be as continuation and preparation for the Fall, and that Marfa could be a really great laboratory environment. At the same time, I’m also in the Llano Estacado and love that amazing laboratory landscape. And so for me, one of the things that’s exciting is if we think about the role of Texas Tech University on the Llano Estacado in West Texas, also operating in El Paso, also operating in Marfa. We can think in a regional territory-based way and thinking about the connections back and forth rather than making satellites like “This is the colony living on Mars. Then we have the colony living on this other space station.” The College of Architecture has a program in El Paso that’s in an active working train station a stone’s throw from the international border. We can leverage an opportunity for the identity of our college as well as our university dealing with the border, dealing with this region, dealing with place. I think Marfa fits really well. I think Land Arts fits really well with that intent. And when I say fits well, I mean, it has the potential to activate and be a resource drawing people, and then also generating a whole myriad of productive works from that. And the catch, of course, with Marfa is that it’s a small community that’s highly desirable now. So the economics have gone a certain way. How we might be able to establish a foothold or kind of set up a space here is the big question that has yet to be answered. But I think it’s possibly solvable. I welcome working on that and the glimmers of hope in that possibility are fantastic. But there’s still lots of work to do.

CHARLOTTE: Well, this was fantastic, Chris. It was so wonderful to hear even more in-depth information about your background, but also about the Land Arts program.

NATHAN: It makes me want to go back. What am I doing up in Canada? [Laughing] Actually, in a way, some of our travels throughout the West, and special towns and sites on our road trips between Salt Lake City and Lubbock, have prompted us to look at new surroundings differently. Like, we are looking for some secret sauce that we hope most places have.

CHARLOTTE: Marfa’s a place I could move to in a heartbeat. I think it has everything that’s so gorgeous about West Texas.

NATHAN: And also in... the getting there.

Chris: My pleasure. Excited to see what comes of this. And just super quick, I was just looking for it, but can’t lay my hands on it. But I can send it to you. You asked about a favorite quote, which normally I hate. I despise, I shouldn’t say “hate.”

CHARLOTTE: Say hate.

Chris: I frown upon favorites questions. I don’t believe in favorites. I find them really tricky questions. But since we just lost Barry Lopez. He’s been on my mind a great deal and he was a friend to the program. And there’s something from his book The Rediscovery of North America that’s really powerful. That talks about the importance of spending time, committing time to places and listening more than proposing within the place. If we treat places, landscapes - he’s talking about like we might treat people - that there’s more to learn if we listen. That we understand that landscapes are much more complex, possibly even more so than language. To me, that’s a really beautiful idea so necessary now.

NATHAN: That’s a beautiful way to wrap this up. Thanks so much, Chris.

Check out Chris’s instagram, and images below as borrowed from the Land Arts program website where you can find MUCH more info!